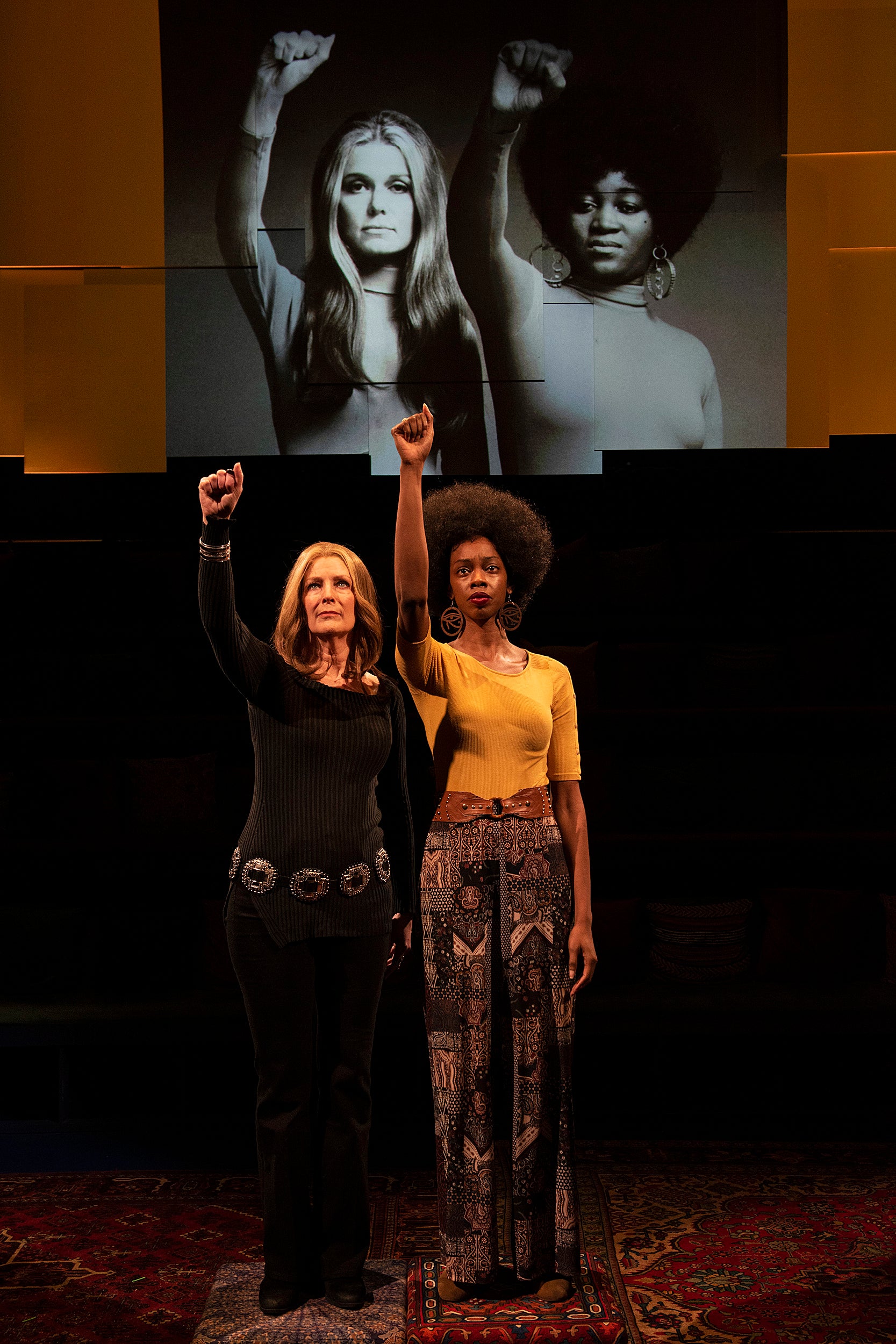

The cast of “Gloria: A Life.”

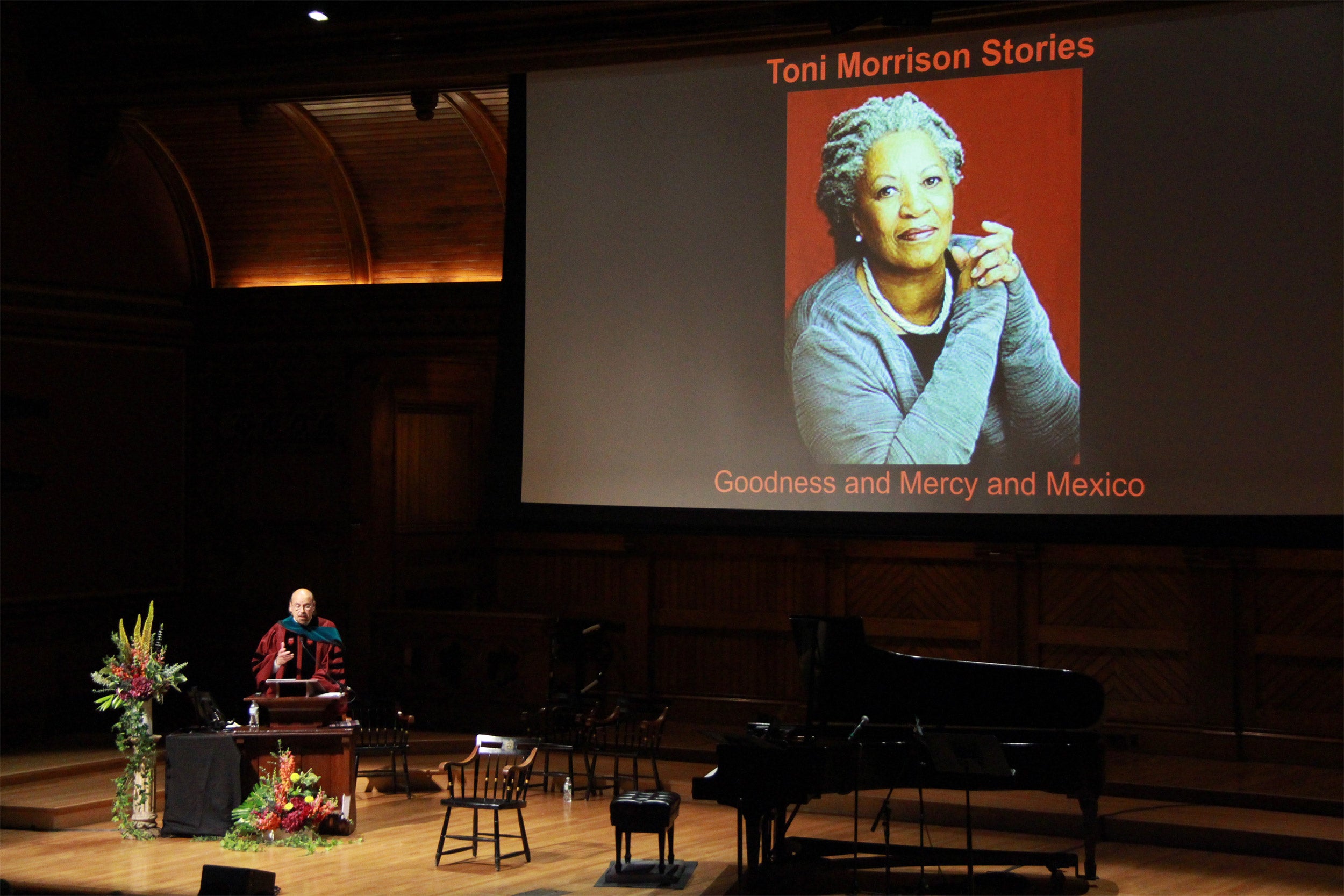

Photos by Ahron R. Foster

How voices shaped Gloria Steinem

New A.R.T. play explores a single life and feminism today through talking circles

Activist, journalist, and feminist Gloria Steinem is woman of many parts. One of the keys to her success, she noted in her 2015 memoir, “My Life on the Road,” is the value she places on personal interaction, listening in particular: “If you want people to listen to you, you have to listen to them,” she wrote. Another would be the near-magical ability of personal stories to teach us about each other and to connect us to one another.

These ideas sit at the heart of “Gloria: A Life,” written by Emily Mann ’74 and directed by Diane Paulus ’88. The play, which begins previews at the American Repertory Theater on Friday and opens Jan. 30, dramatizes the formation as well as the future of the iconic feminist and the movement she spearheaded.

But it took a while for the project to come together.

Steinem, the co-founder of Ms. magazine and one of the original members of the National Women’s Political Caucus in 1971, first considered presenting her life as a play at the urging of her friend Kathy Najimy, the actor. When Steinem, now 85, agreed that it was, perhaps, time to look back, Najimy introduced her to producer Daryl Roth, who brought in both the artistic director of Lincoln Center in New York and playwright Mann, the artistic director of the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, N.J. It was Mann who, working with Steinem, began crafting scenes, resulting in an early attempt that had a very different result than anyone expected.

“We went into a workshop at Lincoln Center with Gloria playing herself,” recalled Mann. “And it was magnificent. And afterwards, Gloria said, ‘I’d rather die than ever do that again.’”

“We had to figure out a new way to go,” the playwright continued. At that point, Paulus got involved, and it soon became clear that keeping the play in its early form and casting an actress as Gloria didn’t quite work. “Without Gloria, it’s just a standard one-woman play,” said Mann.

The solution was to broaden the scope of the show — to incorporate the voices of other women who helped shape Steinem’s. “The more I learned about Gloria, the more I learned about her connection to community,” said Paulus, the Terrie and Bradley Bloom Artistic Director of the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) at Harvard University.

“We realized that we really wanted to bring to life Florynce Kennedy, Bella Abzug, and Wilma Mankiller,” Mann said, citing the activists and politicians whose names may now have been overshadowed by Steinem’s. “We talked about getting a multiracial, multigenerational ensemble to help to tell this tale,” with stories from their own lives and reflections on Steinem and the movement. The voices heard in this biographical first half of the play pave the way for the second, which recalls the talking circles of the small, consciousness-raising groups that pioneered the American feminist movement.

What the team didn’t want, Mann said, were impersonations. Yes, Joanna Glushak, the actor playing Abzug, wears the New York congresswoman’s trademark hat, and Erika Stone, who portrays Mankiller, the first female principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, is of Iroquois and Seneca heritage. But the goal, says Mann, was “channeling.”

Patricia Kalember, who was in the A.R.T.’s production of “The White Card,” portrays Steinem, as she did in the final months of the play’s Off-Broadway run. However, the remainder of the diverse female cast of six each play a variety of roles, including Steinem’s mother. Several also portray men, such as Saul Bellow and Gay Talese. The interaction between these two male literary bastions serves as a stark illustration of the virulent and open sexism Steinem rallied to fight. The setting was a cab, shared by the three writers — two established and one aspiring — in 1963. Leaning across Steinem, Talese explained to Bellow: “You know how every year there’s a pretty girl who comes to New York and pretends to be a writer? Gloria is this year’s pretty girl.”

To see women of various ages and ethnicities in these roles shakes up the story, and makes it fresh, its creators said. “We wanted the soul, the essence of the character, and not the externals,” Mann said of the casting. “The bones of the narrative are the same, but how we did it completely changed.”

What also changed was the structure of the play itself. Building on the A.R.T.’s ongoing practice of hosting discussions, dubbed Act II, the second act of “Gloria” is literally given over to an open discussion.

“Act I, which is the story of Gloria’s life, is the departure point,” said Paulus. Act II invites audience members to talk with the cast and ask questions, either about their own experiences or the events of the day.

“The fourth wall is broken,” said Paulus. “The spirit of being in Gloria Steinem’s living room and being present in a configuration where we can all see each other is retained.

“The whole point is that you matter. That everybody’s story matters. Everybody’s narrative matters. And sharing those narratives is empowering.”