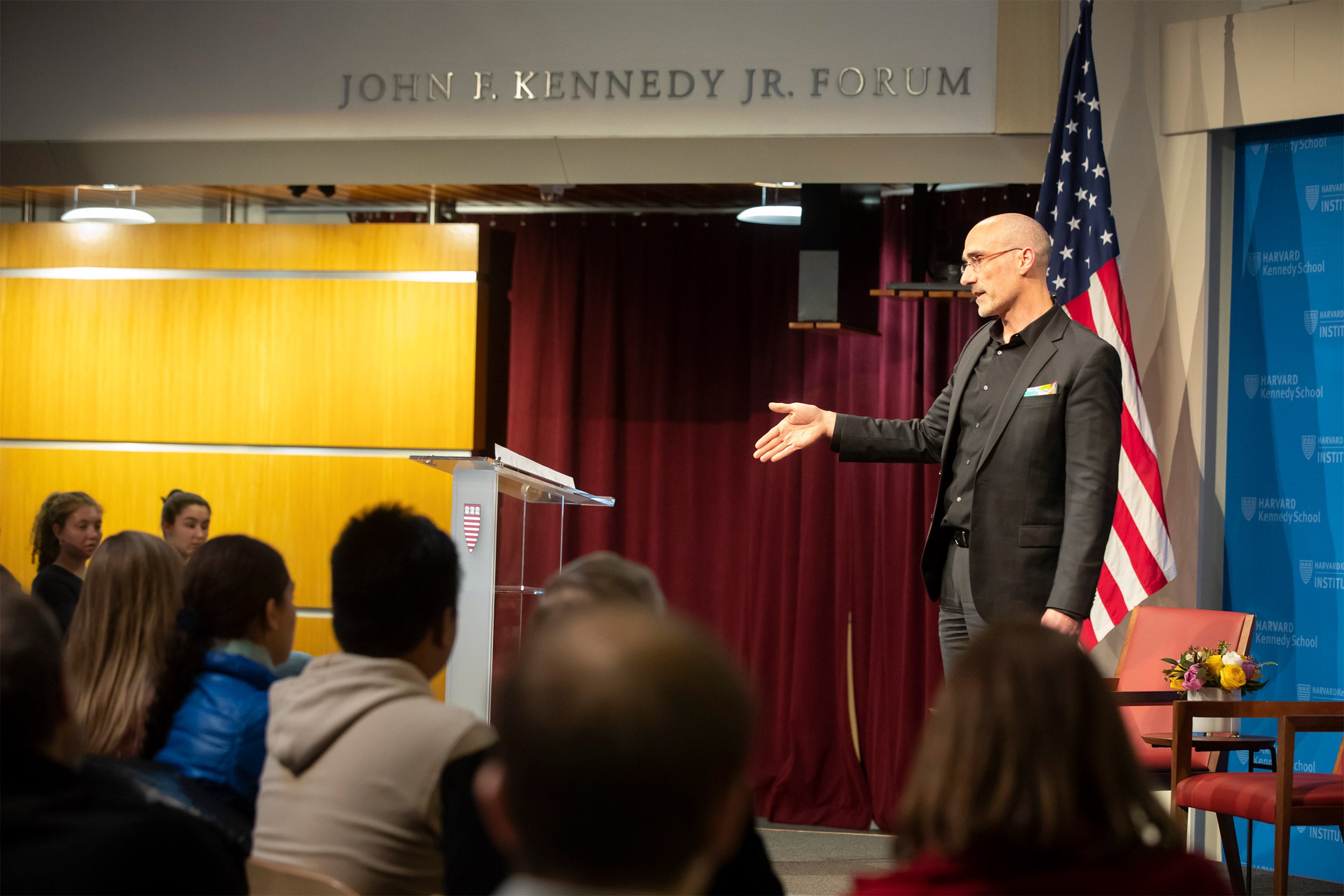

American Enterprise Institute’s Arthur C. Brooks (right) and University Professor Danielle Allen agree to disagree (and sometimes to agree) over the political necessity of love.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

When it comes to politics, what’s love got to do with it?

Danielle Allen and Arthur C. Brooks respectfully address the question

Love might not be all we need, but its lack is surely tearing us apart. That was the point made by Arthur C. Brooks, president of the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute, during a Wednesday evening discussion with James Bryant Conant University Professor Danielle Allen at the Institute of Politics’ John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum.

Love’s potency cannot be underestimated, began Brooks, who is also the Beth and Ravenel Curry Scholar in Free Enterprise at American Enterprise. Discussing the powerful effect of oxytocin — the “love molecule” — and its potential for treating heroin addiction, he moved on to talk about how love of another sort might be able to treat the toxicity of our current political situation.

“Ninety-three percent of Americans hate how divided we’ve become in this country. It’s a love problem. People have stopped talking to relatives,” said Brooks, whose most recent book is “Love Your Enemies.”

“We have a public policy crisis, but we have to be responsible for it,” he continued. Quoting his late mentor, James Q. Wilson, former Shattuck Professor of Government at Harvard, Brooks said, “You really have to remember that public policy never affects people at more than the 5 percent margin of their lives.” When Brooks asked what made up the remainder, Wilson told him, “Mostly just love.”

“If you believe the 5 percent and blow it up to 100 percent, you’re not going to be giving people what they need,” Brooks said. “The revolution doesn’t lie with institutions. The revolution lies within ourselves.”

Love does not mean avoiding conflict, Brooks stressed, citing as an example part of AEI’s mission statement: “competition of ideas is essential to a free society.”

“Competition: That means disagreement,” he said.

Rather, he said what’s needed is loving disagreement that replaces contempt with respect, or, as the Dalai Lama once told him, “with warm-heartedness.”

Dissenting respectfully, or, as Brooks might have put it, with love, Allen argued that the times may be too dire for such restraint. Noting that in the political sphere, we may be facing “actual adversaries,” Allen, who directs the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, pointed out that, “Our conflicts are real and consequential, and the stakes of them are sometimes life-transforming.”

She also called out Brooks’ use of the word “kumbaya,” both in his comments and his book, as shorthand for a faked feel-good camaraderie. “Your book focuses on the contempt we feel in 2019,” she said, citing the battles between red and blue. “But culture is a big, complicated thing that teaches us our moral orientation. Our language is a carrier of contempt. You used ‘kumbaya’ contemptuously. I hear that and I hear my culture being disrespected.” She then played a 1929 recording of a singer from Sea Island, Ga., performing the spiritual with reverence. Brooks accepted the correction.

On several basic points, the two found common ground. Summing up Brooks’ argument, Allen noted that both sides must acknowledge a “deep shared moral consensus,” notably, concern for our country. The second step is to consider one’s adversary in terms of equality. Only then, she noted, would it be possible to “fight with love.”

Brooks agreed, and, in response to a question about the value of protest, brought up the 2017 interaction between Hawk Newsome, president of Black Lives Matter of Greater New York, and Donald Trump supporter Tommy E. Hodges Jr. at a pro-Trump rally in Washington, D.C., that Hodges had organized and Newsome came to protest. Spotting Newsome, who was wearing a Black Lives Matter T-shirt, Hodges offered him two minutes on stage to make his case. Newsome took him up on the offer and introduced himself by saying, “I’m Hawk Newsome, and I’m an American.”

Brooks said that Newsome spent his short time focused on the patriotism that both sides share, saying, “This is America. When something’s not right, you can fix it.”

“If we really want to make America great, we do it together,” he concluded, adding that The Washington Post reported that at Newsome’s words, “And then the crowd cheered.” It was, Brooks said, a perfect “statement of political love.”

“They weren’t saying suddenly, ‘I’m on the other side,’” Brooks said. “They were saying, ‘I like this guy.’ So there’s hope.”