Massachusetts General Hospital researchers have identified markers that can distinguish between major subtypes of lung cancer and accurately identify lung cancer stage. Their work could eventually help physicians decide whether patients need standard treatment or more aggressive therapy.

Unsplash

Better screening for lung cancer

Study may help lead to a blood test to identify patients who warrant low-dose CT screening

By examining blood samples and tumor tissues from patients with non-small-cell lung cancer, investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have identified markers that can distinguish between major subtypes of lung cancer and accurately identify lung cancer stage. Their proof-of-concept test accurately predicted whether the blood samples they examined came from patients with shorter or longer survival following lung cancer surgery, including patients with early stage disease.

Their findings could eventually help physicians decide whether lung cancer patients would benefit from standard treatment or need more aggressive therapy. The study is published in the open-access journal Scientific Reports.

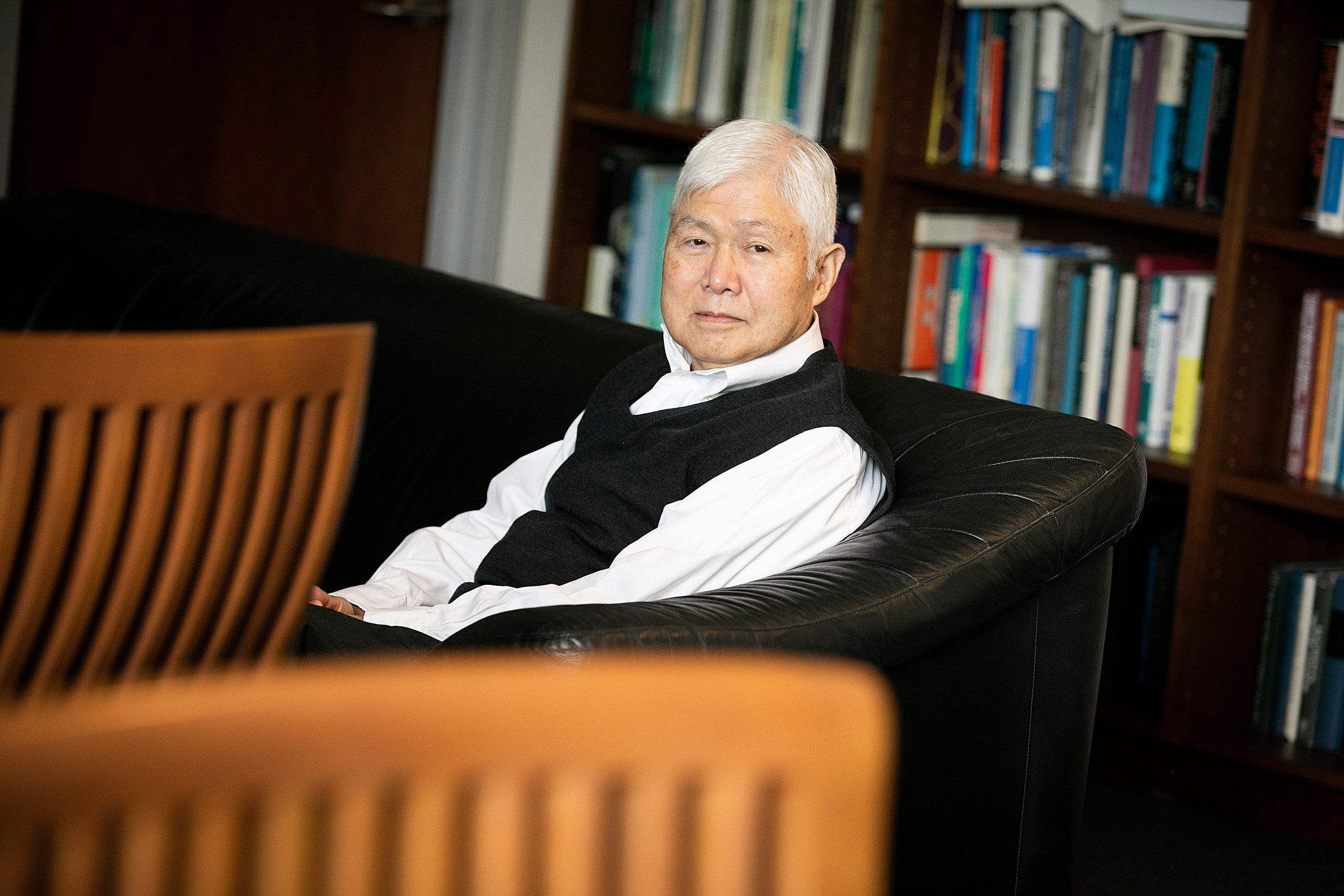

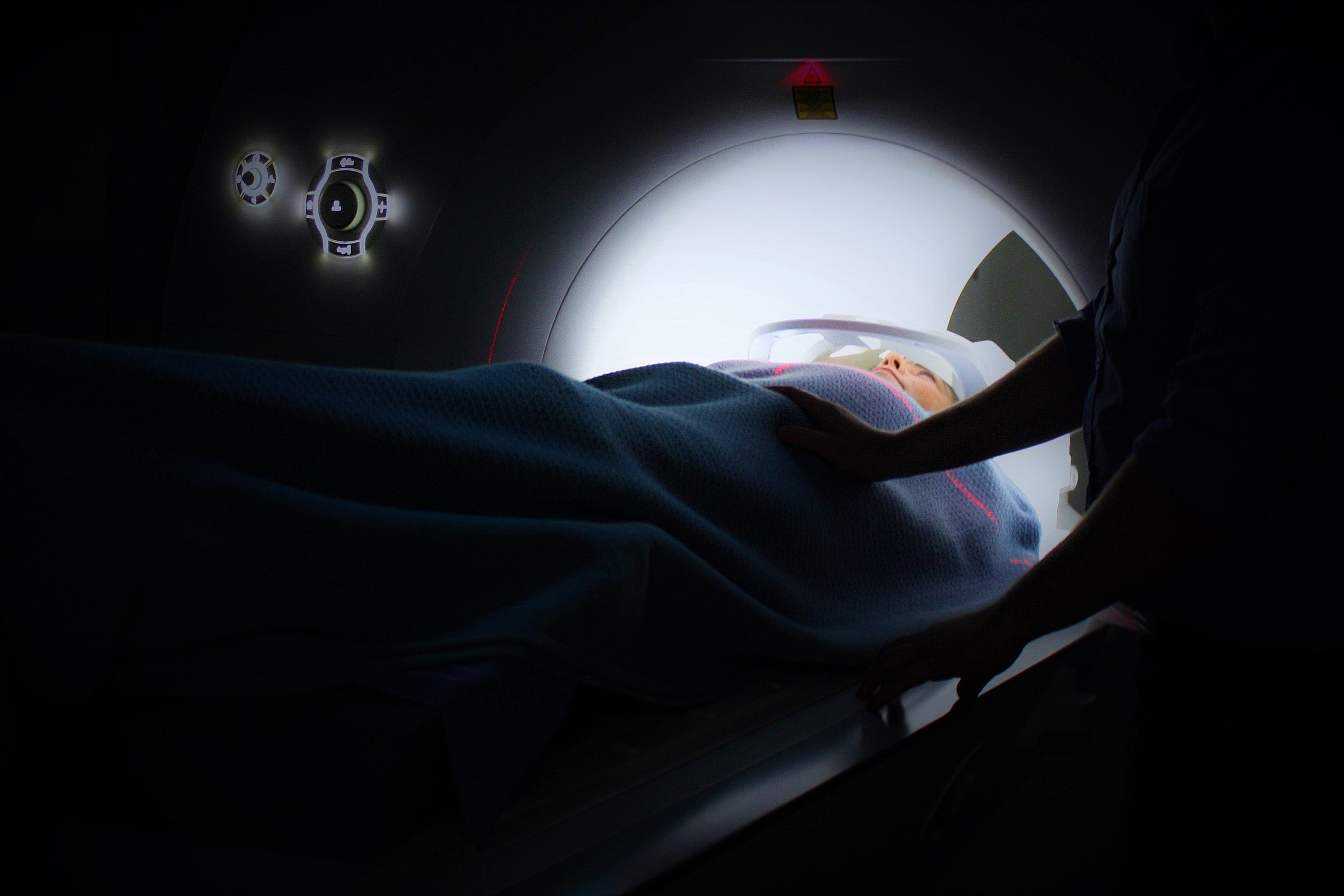

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force currently recommends that middle-aged and older patients with a history of heavy smoking get annual screens for lung cancer with low-dose CT. That test effectively detects small lung tumors but is not used for screening the general population because of the cost and risks of repeated radiation exposure. This points to a need for a low-cost, minimally invasive method for identifying those who may require further CT screening to catch the disease at earlier, more readily treatable stages, said co-principal investigator Leo L. Cheng, an associate biophysicist in the Departments of Pathology and Radiology at MGH and associate professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School (HMS).

“You cannot use CT as a screening tool for every patient or even for every at-risk patient every year, so what we’re trying to do is to develop biomarkers from blood samples that could be incorporated into physical exams, and if there is any suspicion of lung cancer, then we would put the patient through CT,” Cheng said.

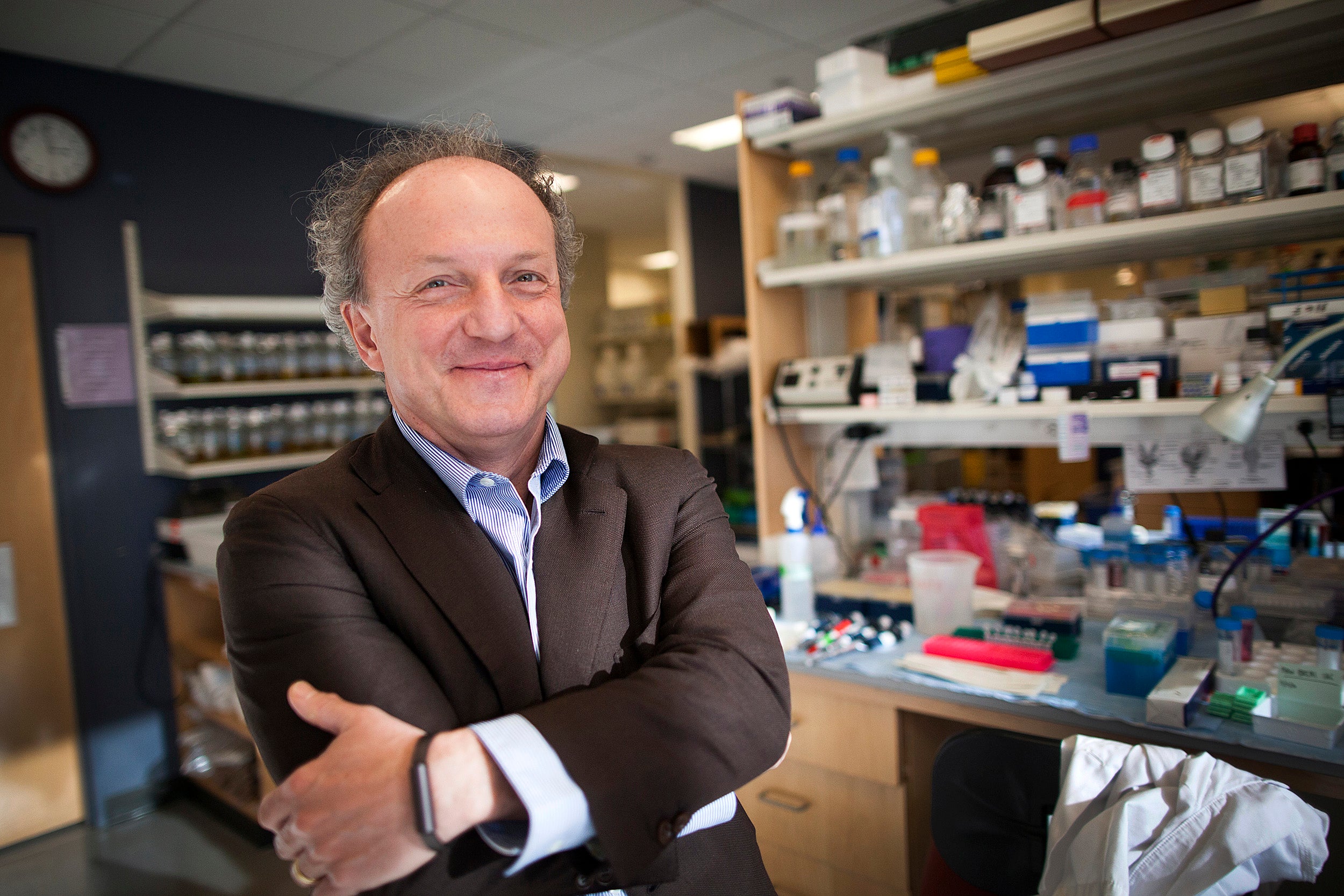

Along with co-principal investigator David C. Christiani, the Elkan Blout Professor of Environmental Genetics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and a physician in the Department of Medicine at MGH, Cheng and other colleagues studied paired blood samples and tumor tissues taken at the time of surgery and looked for metabolomic markers using high-resolution magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), a sensitive technique for characterizing the chemical composition of tissues.

Cheng said that although other researchers have used MRS to identify potential biomarkers of lung cancer in serum, “The uniqueness of our study is that we have paired samples from patients obtained at the same time as surgery.”

The paired specimens came from 42 patients with squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) of the lung, and 51 patients with adenocarcinomas of the lung. The investigators also examined blood samples from 29 healthy volunteers who served as controls. Fifty-eight patients had early lung cancer (Stage I), and 35 had more advanced disease (Stages II, III, or IV).

The experiments were designed to see whether blood samples and tumor tissue samples from the same patient had common features that would identify the presence or absence of lung cancer, discriminate between cancer subtypes, and confirm the diagnostic accuracy of a simple blood test.

The investigators identified specific profiles of metabolites common to both types of samples and showed the differences between the profiles that could signal whether a patient had SCC or adenocarcinoma, which require different treatments. They also found that the profiles could distinguish between early stage disease, which is often highly treatable, and later disease stages which require more aggressive or experimental treatments.

The tests also identified whether samples came from patients who lived an average of 41 months after surgery, or from those who lived longer than 41 months. This finding, if validated in further studies, could identify early on patients at especially high risk for early death, who might benefit from clinical trials of new drugs.

The ultimate goal of the study is to develop a blood test that could be included as part of a standard physical and could indicate whether a specific patient has suspicious signs pointing to lung cancer. Patients identified by the blood screen would then be referred for CT.

Additional co-authors of the Scientific Reports paper are Yannick Berker, Lindsey A. Vandergrift, Isabel Wagner, Johannes Kurth, Andreas Schuler, Sarah S. Dinges, Eugene Mark, and Martin J. Aryee from MGH; Li Su from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Piet Habbel from the Medical University of Berlin; and Johannes Nowak from the University Hospital of Würzburg, Germany.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health and the Massachusetts General Hospital Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging.